Landlords waited longer before approving an application.

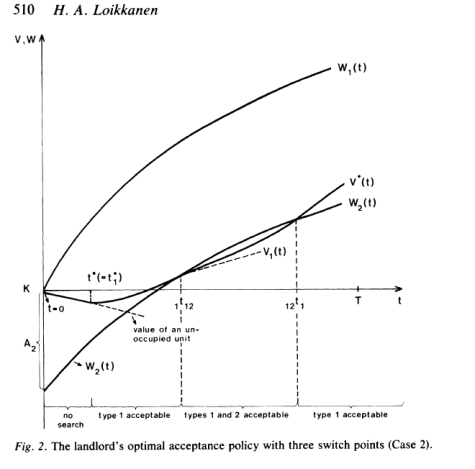

In 1985, Finnish economics scholar Heikki Loikkanen analyzed rent-control policies.

This paper predicted the ranges within which landlords would leave units vacant.

His detailed graph shows that landlords under rent control hold units vacant longer waiting for the perfect applicant.

When prices fall below cost, landlords remove units from the rental market altogether.

Rental availability was reduced during rent control.

Loikkanen’s prediction came true.

During rent control, some owners opted to leave their rentals vacant.

Those who did lease their properties left them vacant longer than usual.

Approved applicants tended to have higher incomes, better credit and no criminal records.

The landlord of this building left his building vacant.

Rich people took at least 20% of rent-controlled dwellings.

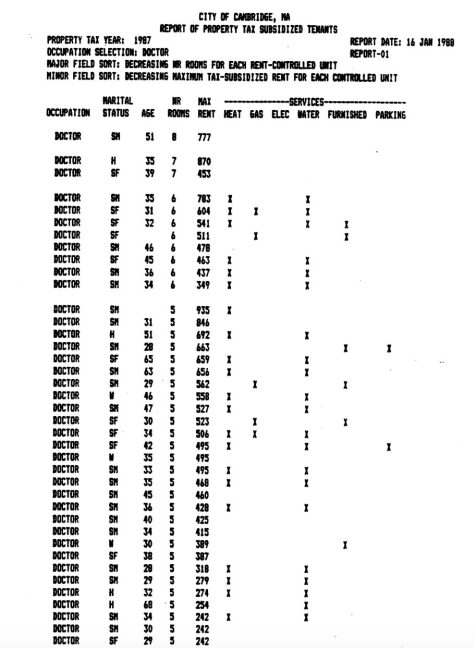

In 1988, Arthur Maringas, a Cambridge resident, became concerned that rent-controlled apartments weren’t going to renters in need.

He launched an independent study of 12,385 rent-controlled properties, or two-thirds of all units.

He counted households headed by 246 doctors, 298 lawyers, 265 architects, 259 professors, 220 engineers, and 2,650 students (1,503 graduate students).

A judge, a prince and the mayor had rent-controlled apartments.

Cambridge tenants in rent-controlled units included Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Judge Ruth Abrams (left);

Prince Frederik of Denmark, a Harvard graduate student at the time (center);

and Cambridge Mayor Kenneth Reeves, who lived in a rent-controlled apartment from his undergraduate Harvard days in the 1970s beyond 1994 (right).

Fewer than 10% of rent control tenants were low income.

It would only become clear following the 1994 statewide vote to ban rent control.

The Cambridge city council devised a plan to transition low-income renters to decontrolled rentals.

Only 9.4% of Cambridge tenants qualified.

The overwhelming majority of rent-controlled units were occupied by middle- and high-income earners, not those who needed rent control.

There was disparate impact on the basis of race.

In Massachusetts, like in America, there was and remains an unfair black-white wealth gap.

There also were and remain unfair differences in credit scores, criminal enforcement and eviction impact.

All of this contributed to an unfair black-white application gap.

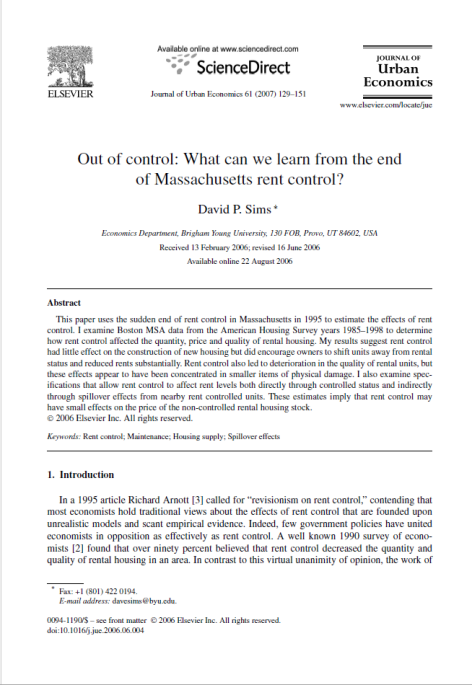

In 2006, David Sims showed in a peer reviewed paper that people of color occupied only 12% of rent controlled apartments, despite representing one-quarter of Cambridge residents.