Local property assessments went down.

Run-down buildings are worth less than nice buildings.

Low rent buildings are worth less than high rent buildings.

Assessed values went down for both reasons.

City tax assessments shrank to match. Rent-controlled properties became less valuable, appraised lower and generated less taxes.

Lower local tax revenue meant higher state aid.

Cities and towns pay for local budgets using a combination of state aid and local taxes.

State aid is calculated according to a formula.

The formula was presented on a “cherry sheet” that showed assessments and receipts.

When property assessments and taxes went down, state aid to those municipalities increased, according to the cherry sheet formula.

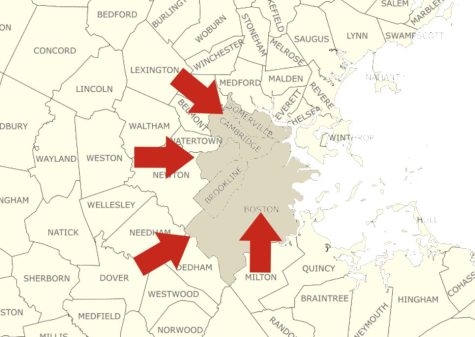

Cities without rent control subsidized cities with rent control.

The budget for state aid is fixed by state revenue.

Because state aid to rent-controlled cities increased, state aid to uncontrolled cities did not.

Other communities effectively subsidized rent control.

For decades, this held back growth in surrounding town budgets.

Schools and general government operations across the state received less funding.

Cambridge assessments regrew by $2 billion because rent control ended.

In Cambridge, some 19,000 properties – close to 40% – were under rent control by 1994.

The total value of all assessed residential real estate was $10 billion, according to a peer reviewed paper published by Autor, Palmer and Pathak in the Journal of Political Economy, 2014.

The study showed that not only did rent controlled properties appreciate faster, but also nearby properties appreciated faster, too.

This is what Autor, Palmer and Pathak call “spillover effect.”

Rent control held back not just single buildings but entire neighborhoods.

When rent control was repealed, all Cambridge properties appreciated $7.8 billion over the next ten years.

One-quarter of this increase, or $1.8 billion, was directly due to rent control, not due to market forces, inflation or any other cause.

That’s the equivalent of nearly $3 billion today.